By Priscilla Robinson

By Priscilla Robinson

Teaching Disease Prevention

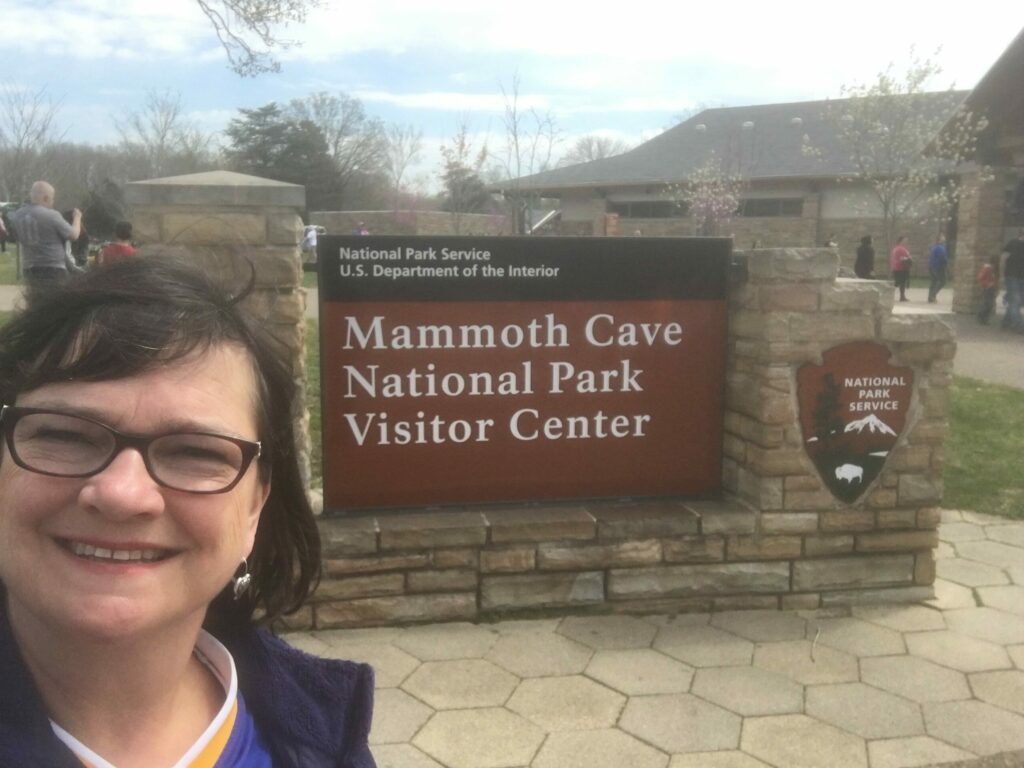

This summer, during a visit to Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, I had an experience that reminded me of why teachers and parents should emphasize good hygiene and disease prevention habits to our children. Whether fungal, bacterial, or viral, pathogens can be real threats to humans—and to wildlife. Preventing the spread of infectious disease is something we can ALL do, if we are taught the proper steps.

At Mammoth Cave National Park, I learned that the bats there are sick and dying. White-Nose Syndrome (WNS) is the culprit. As of 2016, eleven bat species (including four endangered species) have been affected by the fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans. The condition is named for a distinctive fungal growth around the muzzles and on the wings of hibernating bats.

A little brown bat found in a New York cave exhibits fungal growth on its muzzle, ears, and wings. Photo by Al Hicks, NY Department of Environmental Conservation.

White-Nose Syndrome (WNS) was first identified in 2006 in Schoharie County, New York. Over the past decade, it has rapidly spread to more than 25 states in the USA and five provinces of Canada. The disease’s effects on the North American bat population is an unprecedented wildlife disaster. WNS disrupts bats’ natural hibernation cycle, causing them to wake up in winter, when they should be hibernating. It leaves them weak, decreases their flying ability, and thus reduces their access to food sources. To date, millions of bats have died of exhaustion, starvation, and exposure.

It’s important to remember that bats fulfill several important niches for environments around the world. They efficiently eat menacing mosquitoes, pollinate plants, and embellish soils with key nutrients from their guano (bat poop). According to Bat Conservation International, “The Earth without bats would be a very different and much poorer place.”

So how has human activity played a role in this tragic epidemic?

Since no bats normally migrate between Europe and North America, it is likely the fungus was brought to North America by human activities. Pseudogymnoascus destructans has been identified on a number of bats in Europe; however, these findings have not been linked with mass mortalities abroad. One theory is that contaminated soil was brought into the United States via trans-Atlantic air and/or shipping cargo. Another theory is that the fungus simply “hitchhiked” on the clothing of international cave explorers. Scientists continue to struggle to understand how and why White-Nose Syndrome spreads so quickly and how to prevent further exposure in what are now referred to as “clean caves.”

On a personal note, let me confess that I love exploring America’s National Parks. (See my “Let Your Classroom Glow with 100 Candles for Our National Parks” blog for more on this topic.) If there is a cave to explore in the park, even better! Coming across a group of bats in caves has become a rare occurrence for me.

I first encountered the alarm for White-Nose Syndrome in 2012, while visiting the Boyden Cave in Kings Canyon National Park, California. The Rangers were very low key; they simply asked if anyone in our tour group had been to caves east of the Mississippi River. (No one spoke up.)

A few years later, in July 2015, I noted that the Rangers at the Oregon Caves were much more vigilant about requiring visitors to fill out forms before entering the park. They were primarily concerned with our previous whereabouts in an attempt to prevent contamination. Some people were turned away.

During my Mammoth Cave trip in the summer of 2016, I was impressed by the Rangers’ efforts to raise awareness and prevent the further spread of the fungus that causes White-Nose Syndrome. Following our hours in the cave, my group was instructed to walk across a 15-foot wide “pillow” soaked in soap solution as a precaution meant to inhibit the possible spread of spores on our hiking boots. I tried to be vigilant—carefully scuffing my way across the bubbles—but I noticed other visitors taking such long strides that their boots just barely came in contact with the bubbles. It was, I realized, an inconsistent decontamination process.

During my Mammoth Cave trip in the summer of 2016, I was impressed by the Rangers’ efforts to raise awareness and prevent the further spread of the fungus that causes White-Nose Syndrome. Following our hours in the cave, my group was instructed to walk across a 15-foot wide “pillow” soaked in soap solution as a precaution meant to inhibit the possible spread of spores on our hiking boots. I tried to be vigilant—carefully scuffing my way across the bubbles—but I noticed other visitors taking such long strides that their boots just barely came in contact with the bubbles. It was, I realized, an inconsistent decontamination process.

This left me wondering: how do people unknowingly spread diseases to new regions of the world? How can we model and teach our students about the contamination and spread of infectious pathogens?

While White-Nose Syndrome is NOT a threat to people, this isn’t true for many other diseases. No matter what grade level you teach, it’s important to create engaging lessons about the worldwide epidemics for both human and animal populations. After all, we are all sharing the same world.

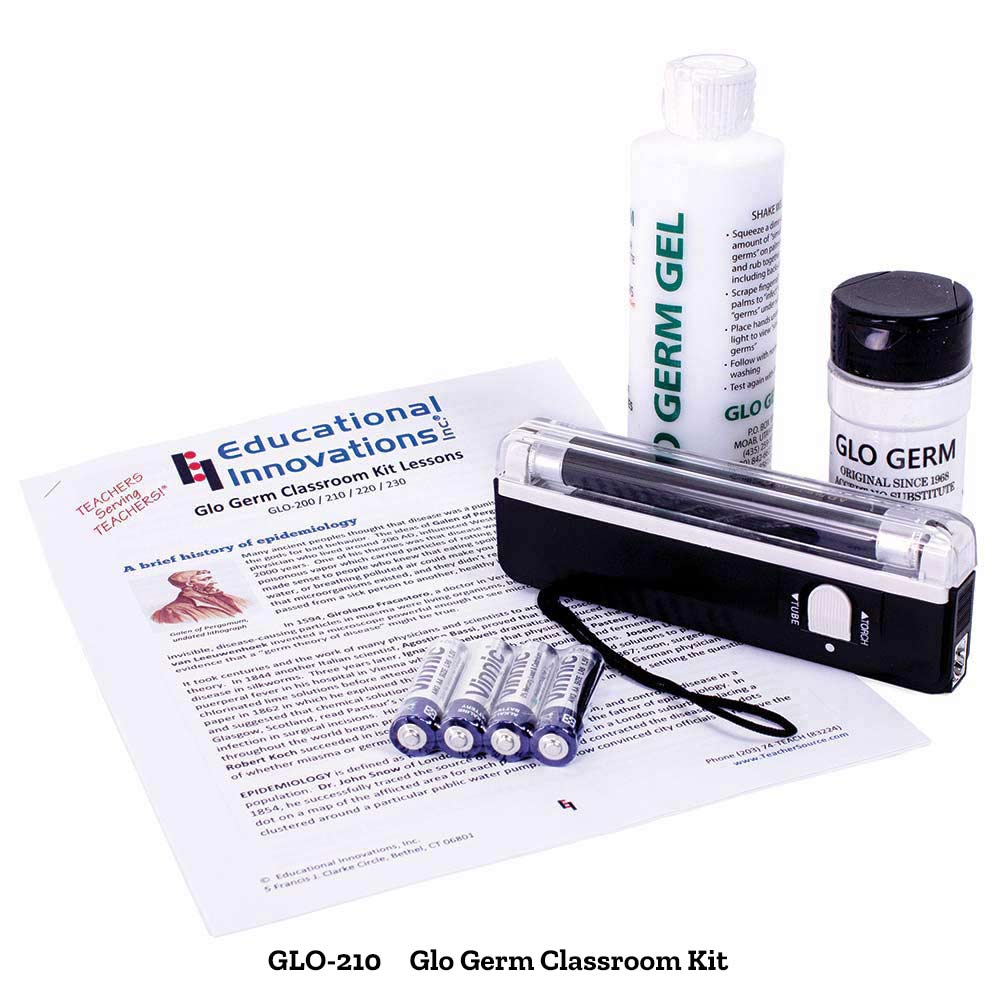

Educational Innovations’ Glo Germ products are perfect for exploring contagious disease and prevention. Glo Germ safely and graphically demonstrates to students and adults alike how germs are spread. Used throughout the United States in schools, hospitals, and food services, Glo Germ consists of an odorless lotion or powder which glows brightly when exposed to ultraviolet light.

You can use the powder on the ground to demonstrate the movement of fungal spores (as in the caves) or else try using the lotion on students’ hands to illustrate how easily viral germs can spread through incidental contact. The dramatic and surprising findings present students of all ages with glowing evidence (literally!) of just how easy contamination occurs.

For other disease prevention lesson ideas for your learners, please refer to my previous blog, “A Firsthand Lesson on Colds, Flu & Infectious Disease.”

You may also want to peruse our GERMS NEWSLETTER, which is brimming with discussion starters, videos, jokes and lessons related to germs and disease transmission.

If you and your students would like to know more about bats and the battle to overcome White-Nose Syndrome, there are several wonderful resources to consider:

White-Nose Syndrome.Org (www.whitenosesyndrome.org)

The National Wildlife Center (www.nwhc.usgs.gov/disease_information/white-nose_syndrome/).

For teachers, classroom resources can be found here: https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/resources/education