By Melanie Pearlman

It’s a scene you don’t often see in a science class: 13- and 14-year-olds flailing their arms about wildly like crazy aliens. It’s only Day One of the activity and they’re hooked by the goofiness allowed. That’s just one of the reasons why I look forward to my Alien Fluids unit every year. It also really sharpens students’ investigative skills and calls on them to think critically and logically.

But how was I to conduct this days-long experimentation activity remotely this year?

How It Starts…

We had just completed a unit on “The Wonder of Water,” physical and chemical properties that are unique to water as both a molecule and a substance. Students learned about electric polarity, molecular cohesion and adhesion, surface tension, and the fact that water expands when it freezes. On the day after the content test, I welcome the students to class, and break them into three groupings. Each group is tasked with their own silly job.

The first group must make up their own spoken language and practice saying “Welcome to our planet,” in that language. They all have to say it together. The second group has to work on how they would convey the idea of water, using only gestures. The third group practices making the sounds of a rocket ship taking off and zooming through the atmosphere.

Welcome to the Alien Planet!

I then present the students with the scenario for our activity. We are getting into a rocket ship and travelling to a far-off planet (I call on group 3 to provide sound effects for this part of the story). After travelling for many months, we finally arrive on a planet that turns out to be inhabited by alien life forms (here group 1 voices their welcome to us). We are very thirsty from our trip and try to ask for water to drink, but the aliens do not understand our language. After many efforts (group 2’s pantomime comes into play), the aliens leave us and return with six jars of clear fluids. Our job is to test these fluids to see which, if any, are indeed water. And we must be certain enough about it to stake our lives on it.

Even with distance learning, we could still experience all of this using Zoom breakout rooms and chat communication. The effect added as much fun to the Zoom call as it normally did to the classroom. From here, though, the plans are that students, in pairs and threes, must come up with three experiments they can do on the fluids we were given. The goal is to find out which of these fluids’ properties match those that we know belong to water.

What’s Next?

In past years, students would hand me their experiment plans and required equipment list at the end of day one, and the next day in class they’d have their supplies and would get to work. Some wanted to freeze fluids and see what happened to their volumes. Others would put drops onto waxed paper to see if they beaded up. Then there were students who would try to mix each fluid with oil, or try to dissolve various solids. Some calculated densities or boiling points.

I always enjoy the ways groups of students talk to each other about their initial results and conduct additional experiments. I usually allot two or three class periods to setting up experiments, getting results and sharing them, and redesigning. But this year, this kind of experimentation wasn’t going to be possible in person. The materials were household items, so students could have them available, but I can’t expect them all to have access to the same items and materials.

This Year… The Remote Alien Lab!

I decided that this year, some of the “playing pretend” would have to extend into the experimentation part of the activity. I wanted to retain the experiment design and collaboration elements of the activity. So I created this Google Slides file, one copy of which was shared with each of the members of an investigation group. That file was their shared digital notebook. Students wrote their experiment plans in it, recorded what they had learned from other groups’ experiments, and designed new experiments.

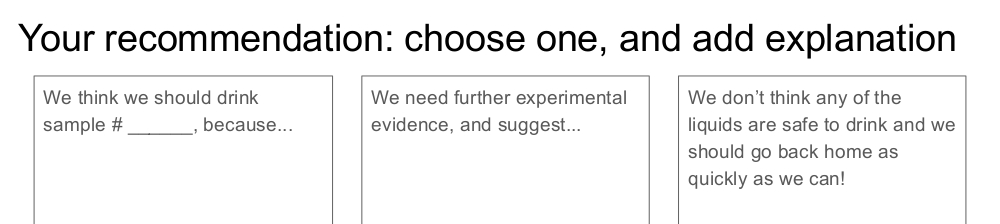

After each day of work, I would read the students’ experiment plans and add my own slide in their file, stating what happened when their experiment was performed. The next day in class they could see their results and were asked to write what they had learned from it. That second day, they discussed together in their lab groups, in breakout rooms, and groups also shared with each other in the whole-class Zoom call. Then each group designed more tests, which were “performed” overnight. They got the results on day 3. Discussion on day 3 was aimed towards a decision: which liquid, if any, can we drink? And how do you know!?

Alien Liquids

I know you were wondering which liquids I present to them. They were salt water, rubbing alcohol, mineral oil, hydrogen peroxide, vinegar, and water. In class, students wear protective goggles, but not gloves, since contact with skin is no problem. During this activity, I teach students how to waft. Of course, they all want to smell each liquid. The vinegar, especially if you stick your nose right in the jar opening, can burn a little.

Some groups choose to exclude the mineral oil or vinegar or even the salt water immediately. (It might be the look or smell of them.) Most groups end up finding the water sample, unless some experimental error kept them from correct results. Some pick salt water, because its properties are pretty close to regular water.

The Results?

This year, online, every group picked water. There weren’t any experimental errors, I realized. The results I gave them were what “should have” happened. That is, the results were based on years of seeing these experiments done. But some were also derived from the fluid’s properties (densities, boiling points, etc.). That’s okay with me. Students were still able to learn so much! They carefully designed experiments, collaborated with others, and synthesized information from various sources to deduce a solution. Plus, they had fun doing it!