by John Frassinelli

by John Frassinelli

Having first seen a “drinking bird” in elementary school myself, I had never forgotten it. Our teacher, I think, had placed one on the windowsill. We had no air conditioning in those days, and the windows actually opened! Air circulated through the room, and that probably influenced the bird. I think it’s too bad that many classrooms are hermetically sealed these days, but we do what we can.

Recently I decided to introduce my first graders to my old friend, the Drinking Bird. I bought a few birds and fooled around with them, making sure each one would “drink” as it was supposed to. I learned that some birds need a bit of adjustment—their centers of mass might be too high or too low. But this is easily remedied by gently twisting the bird’s body and raising (or lowering) it on its metal clasp.

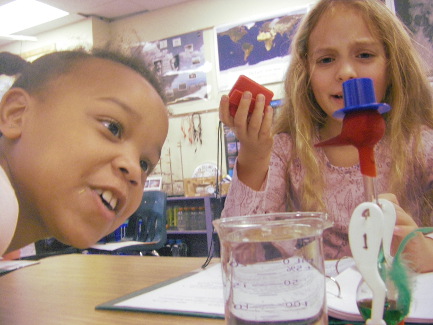

So, when all was ready, I gathered my first graders on our carpet and gently placed the bird’s “beak” into the water. With my index finger, I dipped several drops of water onto the back of the bird’s felt head. Before long, he began drinking. That first drink is always special for the kids, because the slow-rising liquid causes the bird’s head to bob. This teases the children, which they love. And finally it drinks!

As the Drinking Bird’s beak continues to bob in and out of the water, we talk about “evaporation.” All the six-year-olds seem to have an idea or an experience about that. They mention a mud puddle on the playground that dries up on a sunny day… the driveway that returns to “normal” after a rainstorm… and clothes drying on the clothesline (for those whose mothers still do such things!).

To demonstrate that evaporation is a cooling process, we ask for volunteers for an evaporation experiment. Someone is always ready, so I place a cotton ball in some water and then lightly rub the damp cotton on the child’s forearm. “How do you feel?” “Cold!”

We try to lead the kiddos to see that, as the water on the arm turns to gas, it takes something with it. What does it take? As it evaporates, each droplet of water removes some heat. During summer, even if it’s 100 degrees (and it often is here in Memphis), a child will quickly be looking for a towel when he or she climbs out of the pool, especially if the wind is blowing. The wind helps the water to evaporate from our skin, hair, and bathing suits. And it takes away heat! So, of course we feel cold.

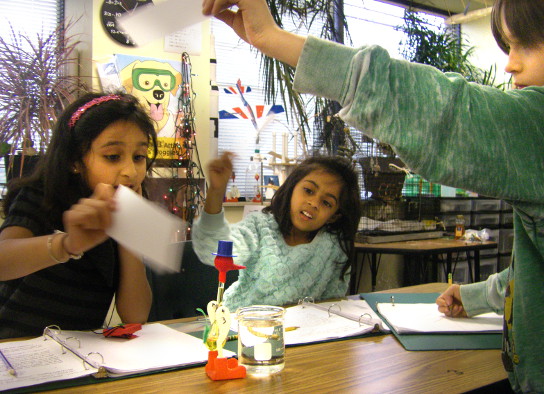

On the second day of our classroom Drinking Bird adventure, each group of two or three children receives their own Drinking Bird. After it begins to drink, we count the number of drinks that occur in three minutes. We record our information in a data table. And we remind the kiddos about the swimming pool, the towel, and how they feel cold when they get out of the water.

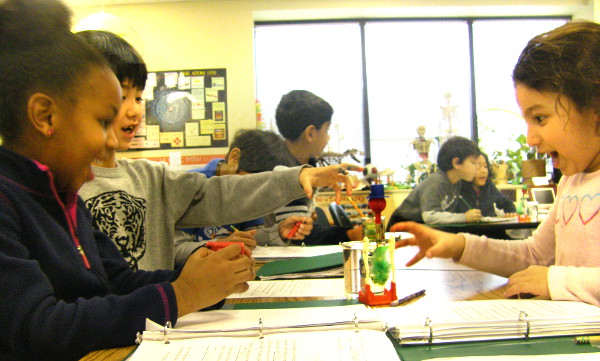

We repeat the experiment. We set the timer for another three minutes, but this time the children are given an index card with instructions to “fan the bird.” No touching!

Might this affect the frequency of drinking? The kids are delighted to find that it does! They count the drinks enthusiastically. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a situation where the frequency of drinking hasn’t increased with fanning. Here are some actual data from one of my classes:

|

TEAM |

NO FAN | WITH FAN |

|

1 |

8 | 16 |

| 2 | 12 |

21 |

|

3 |

15 | 36 |

|

4 |

6 |

10 |

| 5 | 5 |

11 |

|

6 |

10 |

30 |

| 7 | 10 |

20 |

As you can see, the results of our little experiment were consistent and (I think) fairly impressive from a statistical standpoint. As a class, our un-fanned birds totaled 66 drinks in three minutes; our fanned birds totaled 144. That’s an increase of 218%!

I’ve often thought that, if I ever teach high school science again, I would do this same experiment and throw in a variable or two. But with my first graders, we sort of automatically had some constants and controls: the birds, the experimenters, the time of day, the duration of the experiment, and so on. Plus, it’s just plain fun! The birds look a little silly, provide everyone with an excuse to giggle, and teach a bit of science. What could be better?

Author’s Note: This is my 33rd year of teaching. I presently teach elementary science in grades 1, 2, 3, and 4. Before that, I taught middle school science and math for 18 years, and high school physical science, physics, and environmental chemistry for six years. I was pretty happy teaching high school when the offer came to teach elementary. At first, I didn’t even consider it. But as a few weeks passed, I thought of what a great adventure it might be. And it has been! I have also taught for the University of Mississippi at Rainwater Observatory (“Astronomy for Teachers”) and offer occasional workshops and summer camps. The time has passed very quickly! The younger kids are absolute sweetie-pies and just love science. If you’re willing to roll with it, be a little silly, develop some patience, and work hard, it’s quite rewarding. I also have a website for my students & parents, www.lausannescience.com. Thanks for reading!